Source:-thetimes.co.uk

After a moment of high comedy during Sri Lanka’s innings at Durham, when the running between the wickets resembled a Laurel and Hardy slapstick routine, the cameras panned to Mickey Arthur. Hands on hips, lips curled, Sri Lanka’s coach looked momentarily like a temping schoolteacher put in charge of a class he did not recognise nor could control. Another fine mess, he seemed to be thinking, or, to put it more bluntly, in today’s lingo: “WTAF?”

In mid-innings confusion during the first ODI against England, Chamika Karunaratne and Binura Fernando, two wet-behind-the-ears internationals, found themselves at the same end. A bullet throw from Liam Livingstone in the deep burst through Jonny Bairstow’s gloves, to give rise to a rush to see who could win the scramble to the non-striker’s end first. It was just one snapshot of a difficult day, for sure, but it encapsulated the decline in the basics of a team once renowned for setting trends and standards in cricket.

Arthur is a well-travelled, well-respected coach. From South Africa to Australia to Pakistan and now to Sri Lanka, via some franchised leagues, he has seen just about everything cricket has to offer. He is an optimist, one of the game’s most ebullient characters, who loves the rough and tumble of the dressing room. No job too small; no mess too big.

Sri Lanka’s totals have been overhauled easily in three one-day matches by England — and when it was the touring side’s turn to chase 181 in the third T20 at the Ageas Bowl, they were skittled for 91

LINDSEY PARNABY/AFP

One feels for him, though, given the scale of his present challenge: all cricketing nations go through cycles, peaks and troughs that fix themselves over time, but the extent of Sri Lanka’s decline is deeply worrying.

The most recently updated World Super League table, the process by which qualification for the 2023 World Cup is decided, makes for grim reading. Sri Lanka sit bottom of the 13 teams, behind Afghanistan, Netherlands, Ireland and Zimbabwe, having won only one match. Although this cycle is in its early days, on present form they will not qualify automatically. In the recently concluded World Test Championship, Sri Lanka finished seventh out of nine, with only West Indies and Bangladesh below them.

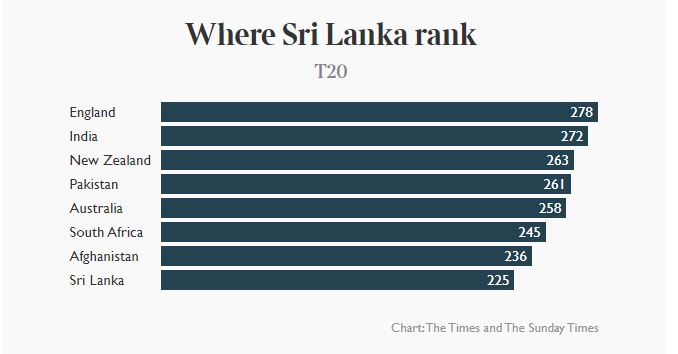

The ICC rankings reflect a longer period of time, pre-Covid, and are therefore a more reasonable assessment of a team’s standing. Sri Lanka are eighth in Tests and T20s and ninth in ODIs. The decline of a team that once bossed ICC events, competing in five finals between 2007 and 2014, has been dramatic and nothing we have seen in the past two weeks — Sri Lanka lost the T20 series 3-0 to England before being well beaten in that first ODI on Tuesday — suggests those positions are misplaced. It has looked one of the least competitive teams to come here for some time.

That this year is an anniversary of the greatest moment in Sri Lanka’s cricketing history offers context into the present woes. On a steamy night in Lahore 25 years ago they claimed the World Cup by hammering Australia, as they had most other teams in that tournament. The winning runs were scored by the architect of that triumph, Arjuna Ranatunga, who was embraced immediately by the non-striker, Aravinda de Silva, a batsman of magical gifts of touch and timing.

De Silva is head of a technical advisory committee that includes another member of that famous win, Muttiah Muralitharan, the champion off spinner. In the commentary box a few days earlier, another member of the committee, Kumar Sangakkara, was left momentarily speechless — a rare state of being — when asked whether these were the best players the country could produce.

There were other ghosts of that World Cup win in Durham this week. Romesh Kaluwitharana, now a little more thickset than the whip-thin wicketkeeper who dazzled at the top of the order with Sanath Jayasuriya, is a selector. Chaminda Vaas, the outstanding left-arm swing bowler, is the bowling coach. At least, unlike the batting coach, Grant Flower, he has some raw materials to work with. Wanindu Hasaranga, the leg spinner, and Dushmantha Chameera, the fast bowler, are good prospects.

The standard of batting in the T20s and opening ODI, though, was really poor. It was not helped in Durham by the banishment of three established players — Niroshan Dickwella, Kusal Mendis and Danushka Gunathilaka — who had broken the team’s Covid protocols. If it seemed, on the face of things, a harsh punishment to send them home, it was a reflection on the decline in general discipline over the past few years. From his days as Australia coach, Arthur is no stranger to a “line in the sand” moment, and this, for Sri Lanka, seemed to be it.

Sri Lanka were thrilling and innovative en route to becoming world champions in 1996, as our correspondent found out in the quarter-final

JOHN GILES/PA

It resulted in a threadbare team in Durham, with the captain, Kusal Perera, the only man to have played more than 30 ODIs. The turnover of players and captains has been high, as it tends to be in periods of struggle. Before the T20 series, Sri Lanka had used 25 players in the previous dozen matches. The former England coach, Duncan Fletcher, would talk of a “critical mass” of senior players, essential to the functioning of any successful international team, and there is little evidence of that.

There are deeper problems. Tom Moody, recently installed as the director of cricket, has spoken of the need to reform a domestic structure based around 24 first-class teams (increased from ten, five years ago) that has resulted in talent being spread too thinly. “It is not a system that supports excellence,” Moody said after taking up the job and making recommendations for a fundamental overhaul. “Once you provide a system that encourages excellence, you allow talent — which this country is not short of — to thrive.”

Administration of the game seems dysfunctional and sclerotic. A sport that is a passport for recognition, meaning and money may find itself vulnerable to all kinds of birds of prey, with a number of investigations into corruption in the past few years by the ICC involving Sri Lanka. Three years ago, the sports minister was quoted as saying the ICC viewed administration of the game in the country as “corrupt from top to bottom”. In 2019, the ICC’s anti-corruption unit offered an amnesty in response to the specific challenges faced there.

Given the modern-day problems, it would be easy to forget that passion for the sport continues, in streets, schools, colleges and clubs. In the novel Chinaman, Shehan Karunatilaka, the Sri Lankan author, muses on the existential nature of sport. Cricketers, he thinks, cannot do anything of practical value but they can bring an entire nation to its feet for a moment in time — as our footballers are doing now.

Sri Lanka’s players have managed that before, too; the hope is they will be able to do it again.